Summary

Narration describing the author’s experience learning Kyudo, the Japanese martial art of archery, from Awa Kenzo in the 1920s. The story is interspersed with attempts at explaining Zen philosophy.

Highlights

On simplicity and understanding:

[…] what I can not say quite simply and without recourse to mystic jargon has not become sufficiently clear and concrete even to myself.

For them the contest consists in the archer aiming at himself, and yet not at himself, in hitting himself, and yet not himself, and thus becoming simultaneously the aimer and the aim, the hitter and the hit.

In Buddhism and yoga this is a common model: while in deep meditation observer, observing, and observed merge or disappear and you realize the self.

On the limits of words and intellectual knowledge, and the need for a teacher:

The reason for this painful feeling of inaccessibility lies, to some extent, in the style of exposition that has hitherto been adopted for Zen. No reasonable person would expect a Zen adept to do more than hint at the experiences which have liberated and changed him, or to attempt to describe the unimaginable and ineffable “Truth” by which he now lives.

[…]

The Zen adept has an insuperable objection to giving any kind of instructions for the happy life. He knows from personal experience that nobody can stay the course without conscientious guidance from a skilled teacher and without the help of a Master.

[…]

disappointed and discouraged, I gradually came to realize that only the truly detached can understand what is meant by “detachment”, and that only the contemplative, who is completely empty and rid of the self, is ready to “become one” with the “transcendent Deity”.

[…]

there is and can be no other way to mysticism than the way of personal experience and suffering, and that, if this premise is lacking, all talk about it is so much empty chatter.

[…]

why the Zen adept shuns all talk of himself and his progress. Not because he thinks it immodest to talk, but because he regards it as a betrayal of Zen. Even to make up his mind to say anything about Zen itself costs him grave heart−searchings. He has before him the warning example of one of the greatest Masters, who, on being asked what Zen was, maintained an unmoving silence, as though he had not heard the question.

Perhaps, the reason for this economy of words is similar to the one given in vipassana and yoga: words agitate the mind because they activate memories, and when that happens it’s harder to see reality as it is.

Steep is the way to mastery. Often nothing keeps the pupil on the move but his faith in his teacher, whose mastery is now beginning to dawn on him. He is a living example of the inner work, and he convinces by his mere presence.

I’ve read many accounts of people who felt something extraordinary in the presence of great spiritual masters. When I was a teenager I attended Sivananda Yoga center classes in Madrid with a sannyasi teacher and I have vague memories of feeling something special. However in recent years I’ve attended several Vipassana meditation retreats with teachers like Yuval Harari and I don’t remember feeling something similar. Maybe as a teenager I imagined things? Maybe now I’ less perceptive? I don’t know.

However I looked at it, I found myself confronted by locked doors, and yet I could not refrain from constantly rattling at the handles.

I couldn’t have put it into words more clearly. I have experienced this many times when reading cryptic texts like for example the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali and Daoist texts.

Let go of the desire to be in control:

[…] archery is not meant to strengthen the muscles. When drawing the string you should not exert the full strength of your body, but must learn to let only your two hands do the work, while your arm and shoulder muscles remain relaxed, as though they looked on impassively. Only when you can do this will you have fulfilled one of the conditions that make the drawing and the shooting “spiritual”.

One of the things I enjoyed most from the book are the references to the importance of breathing:

For through this breathing you will not only discover the source of all spiritual strength but will also cause this source to flow more abundantly, and to pour more easily through your limbs the more relaxed you are." And as if to prove it, he drew his strong bow and invited me to step behind him and feel his arm muscles. They were indeed quite relaxed, as though they were doing no work at all.

[…]

for better practice and control, he made us combine it with a humming note.

[…]

The breathing in, the Master once said, binds and combines, by holding your breath you make everything go right, and the breathing out loosens and completes by overcoming all limitations. But we could not understand that yet.

[…]

Each of them began with breathing in, was sustained by firm holding of the down−pressed breath, and ended with breathing out. The result was that the breathing fell into place spontaneously and not only accentuated the individual positions and hand−movements, but wove them together in a rhythmical sequence depending, for each of us, on the state of his breathing capacity.

When, to excuse myself, I once remarked that I was conscientiously making an effort to keep relaxed, he replied: “That’s just the trouble, you make an effort to think about it. Concentrate entirely on your breathing, as if you had nothing else to do!”

I learned to lose myself so effortlessly in the breathing that I sometimes had the feeling that I myself was not breathing but “strange as this may sound” was being breathed. And even when, in hours of thoughtful reflection, I struggled against this bold idea, I could no longer doubt that the breathing held out all that the Master had promised.

[…]

The breathing in, like the breathing out, is practiced again and again by itself with the utmost care. One does not have to wait long for results. The more one concentrates on breathing, the more the external stimuli fade into the background.

[…]

if one then concentrates on breathing one soon feels oneself shut in by impermeable layers of silence. One only knows and feels that one breathes. And, to detach oneself from this feeling and knowing, no fresh decision is required, for the breathing slows down of its own accord, becomes more and more economical in the use of breath, and finally, slipping by degrees into a blurred monotone, escapes one’s attention altogether.

[…]

The only successful way of rendering this disturbance inoperative is to keep on breathing quietly and unconcernedly, to enter into friendly relations with whatever appears on the scene, to accustom oneself to it, to look at it equably and at last grow weary of looking. In this way one gradually gets into a state which resembles the melting drowsiness on the verge of sleep.

The “humming” technique is also used in yoga where it’s called ujjayi pranayama.

The author reached the following milestone after one year of practice:

I managed to draw the bow and keep it drawn until the moment of release while remaining completely relaxed in body, without my being able to say how it happened.

[…]

Had he begun the lessons with breathing exercises, he would never have been able to convince you that you owe them anything decisive. You had to suffer shipwreck through your own efforts before you were ready to seize the lifebelt he threw you. Believe me, I know from my own experience that the Master knows you and each of his pupils much better than we know ourselves. He reads in the souls of his pupils more than they care to admit.

I feel the truth of these words, I don’t know why:

For the performance of these exercises it is sufficient that the pupil should understand, or in some cases merely guess, what is demanded of him.

On the need to do without doing:

By letting go of yourself, leaving yourself and everything yours behind you so decisively that nothing more is left of you but a purposeless tension.

[…]

The right shot at the right moment does not come because you do not let go of yourself. You do not wait for fulfillment, but brace yourself for failure. So long as that is so, you have no choice but to call forth some thing yourself that ought to happen independently of you, and so long as you call it forth your hand will not open in the right way ˙ like the hand of a child: it does not burst open like the skin of a ripe fruit.

[…]

“The right art”, cried the Master, is purposeless, aimless! The more obstinately you try to learn how to shoot the arrow for the sake of hitting the goal, the less you will succeed in the one and the further the other will recede. What stands in your way is that you have a much too willful will. You think that what you do not do yourself does not happen.

[…]

If the shot is to be loosed right, the physical loosening must now be continual in a mental and spiritual loosening, so as to make the mind not only agile, but free:

between these two states of bodily relaxedness on the one hand and spiritual freedom on the other there is a difference of level which cannot be overcome by breath−control alone, but only by withdrawing from all attachments whatsoever, by becoming utterly egoless: so that the soul, sunk within itself, stands in the plenitude of its nameless origin.

On the patience of a good master who knows experience is the only way to teach certain things:

Shunning long−winded instructions and explanations, the latter contents himself with perfunctory commands and does not reckon on any questions from the pupil. Impassively he looks on at the blundering efforts, not even hoping for independence or initiative, and waits patiently for growth and ripeness. Both have time: the teacher does not harass, and the pupil does not overtax himself.

The goal is the way:

[…] what impels him to repeat this process at every single lesson, and, with the same remorseless insistence, to make his pupils copy it without the least alteration? He sticks to this traditional custom because he knows from experience that the preparations for working put him simultaneously in the right frame of mind for creating. The meditative repose in which he performs them gives him that vital loosening and equability of all his powers, that collectedness and presence of mind, without which no right work can be done.

This clarity describing subtle psychological experiences, both from the master and the student, is what I wish I could convey when I journal about my meditative experiences:

You remained this time absolutely self−oblivious and without purpose in the highest tension, so that the shot fell from you like a ripe fruit.

[…]

“Your arrows do not carry,” observed the Master, “because they do not reach far enough spiritually. You must act as if the goal were infinitely far off. For master archers it is a fact of common experience that a good archer can shoot further with a medium−strong bow than an unspiritual archer can with the strongest. It does not depend on the bow, but on the presence of mind, on the vitality and awareness with which you shoot. In order to unleash the full force of this spiritual awareness, you must perform the ceremony differently: rather as a good dancer dances. If you do this, your movements will spring from the centre, from the seat of right breathing.

[…]

You are under an illusion “, said the Master after a while, “if you imagine that even a rough understanding of these dark connections would help you. These are processes which are beyond the reach of understanding.”

We practised in the manner prescribed and discovered that hardly had we accustomed ourselves to “dancing” the ceremony without bow and arrow when we began to feel uncommonly concentrated after the first steps. This feeling increased the more care we took to facilitate the process of concentration by relaxing our bodies.

[…]

Although he dealt in mysterious images and dark comparisons, the meagrest hints were sufficient for us to understand what it was about.

On the need to let go of the desire to be in control:

The more he tries to make the brilliance of his swordplay dependent on his own reflection, on the conscious utilization of his skill, on his fighting experience and tactics, the more he inhibits the free “working of the heart.”

[…]

The pupil must develop a new sense or, more accurately, a new alertness of all his senses, which will enable him to avoid dangerous thrusts as though he could feel them coming. Once he has mastered this art of evasion, he no longer needs to watch with undivided attention the movements of his opponent, or even of several opponents at once. Rather, he sees and feels what is going to happen, and at that same moment he has already avoided its effect without there being “a hair’s breadth”.

On emptiness and doing without doing in swordmanship:

He takes this non−observation very seriously and controls himself at every step. But he fails to notice that, by concentrating his attention on himself, he inevitably sees himself as the combatant who has at all costs to avoid watching his opponent. Do what he may, he still has him secretly in mind.

[…]

And here too “It” is only a name for something which can neither be understood nor laid hold of, and which only reveals itself to those who have experienced it.

[…]

Perfection in the art of swordsmanship is reached, according to Takuan, “when the heart is troubled by no more thought of I and You, of the opponent and his sword, of one’s own sword and how to wield it no more thought even of life and death. All is emptiness: your own self, the flashing sword, and the arms that wield it. Even the thought of emptiness is no longer there.”

From this absolute emptiness, states Takuan, “comes the most wondrous unfoldment of doing”.

On the conquest of fear that comes with mastery of swordsmanship:

The swordmaster is as unselfconscious as the beginner. The nonchalance which he forfeited at the beginning of his instruction he wins back again at the end as an indestructible characteristic. But, unlike the beginner, he holds himself in reserve, is quiet and unassuming, without the least desire to show off. Between the stages of apprenticeship and mastership there lie long and eventful years of un−tiring practice. Under the influence of Zen his proficiency becomes spiritual, and he himself, grown ever freer through spiritual struggle, is transformed.

[…]

Like the beginner the swordmaster is fearless, but, unlike him, he grows daily less and less accessible to fear.

[…]

He no longer knows what fear of life and terror of death are.

[…]

Those who do not know the power of rigorous and protracted meditation cannot judge of the self−conquests it makes possible.

[…]

At any rate the perfected Master betrays his fearlessness at every turn, not in words, but in his whole demeanour: one has only to look at him to be profoundly affected by it. Unshakable fearlessness as such already amounts to mastery, which, in the nature of things, is realized only by the few.

In yoga one of the five obstacles, or “klesas”, to realizing the Self is fear of death. Once you uncover your true self, fear is said to disappear because you realize your immortal nature.

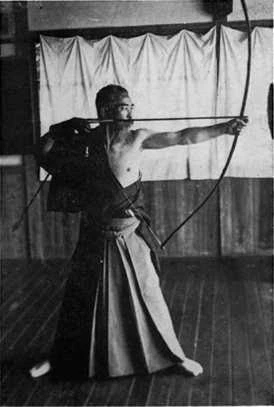

Awa Kenzo (and a video of him)

Connections

- Teachers: Stand on the shoulders of giants, honor the heavy cost they paid with their lives and don’t waste time.

- Mastery: I feel “elevated” every time I face deep mastery or vicariously experience emptiness. I have never been interested in archery or swordsmanship, but I couldn’t put the book down because it felt magic.

- Embodied knowledge: trust it (The Inner Game of Tennis), get the mind out of the way.

- Emptiness: Zen, Daoism, yoga’s ultimate state of citta vritti nirodha or mental stillness.

- Storytelling: I learned about the book thanks to an article that described how Eugen’s teacher, Awa Kenzo, hit a bullseye, then with a second arrow he hit the first arrow, at night. We’re wired for stories, practice this skill, use it to communicate more effectively.

- Breath: We breathe around 20k times per day. Master pranayama, any permanent improvement, no matter how small, is going to compound enormously.

Why (not?) trust the author?

The author, Eugen Herrigel, was a German nazi philosopher; Awa Kenzo never practiced Zen or studied under a Zen master, and the translator between Eugen and Awa complained about the challenge translating Awa’s frequently cryptic instructions. Most of what Eugen learnt about Zen, he did based on D.T. Suzuki’s writings. As Away’s biographer, Yamada Shoji, warns in his The Myth of Zen in the Art of Archery take the Zen references with a grain of salt.

That said, what I value about the book are the author’s observations about his practice or his teacher, which elevate and inspire me every time I read them. I still consider the book a gem.

How do I grow from this?

I’ve copied some of these highlights to my commonplace, to re-read them regularly and use them as references (in the sense described in Awakening the Giant Within by Tony Robbins).

The book strengthened my belief that mastering fundamental skills like breathing, equanimity, and “doing without doing” (Bhagavad Gita) are the highest ROI skills I can practice.

I will refer to the book when I’m trying to journal about my meditative experiences.

Remember to judge ideas on their own. You don’t throw everything Aristotle said into the trash because he believed slavery was natural.