There are many exercises you can try to improve your performance but they are not all equally useful. Besides that exercises that were useful in the past may not be useful anymore after you reach a certain skill level. If you don’t measure your progress you are in the dark and you could be wasting precious practice time. And when you are by yourself measuring is the only objective coach you have to tell you this.

Misunderstandings about measurements

A commonly held but wrong belief about measuring is that all measurements need to be very precise to be useful but that’s not the purpose of measuring. We measure in order to reduce uncertainty and, in particular in our case, uncertainty about how much we are improving. Anything that reduces uncertainty is useful regardless of how precise it is.

Another common misunderstanding is that there are many variables that can’t be measured like happiness or health. However that’s not true. If you care about improving for example your health, it’s because you can tell the difference between bad health and good health. And if you can tell the difference it’s because there are differences which means there is something you can measure.

One way of dealing with these important but hard to measure variables is to think of other variables that are correlated with the one you are interested in. For example, when I wanted to improve my health after an stressful period at work I measured the following yes/no variables on a daily basis:

- No stomach or intestine pain (that’s the part of my body that shows signs of stress first)

- Am I well-rested?

- Did I do at least 30 min of intense aerobic or anaerobic exercise?

- Did I do yoga and pranayama?

- Did I only do relaxing tasks after 8pm?

- Did I eat with moderation and felt slight hunger?

- Did I eat only healthy foods?

- Did I meditate?

In my particular case the more questions from that list that I can answer with “yes”, my health score, the healthier I feel. If, over time, my health score decreases I know that I need to take action. And this is more precise than the subjective feeling of how healthy I feel which can be affected by many factors other than my actual health.

Measurement principles

When measuring for performance keep in mind the following principles:

Any measurement that reduces your uncertainty is useful, it doesn’t need to be as precise as an atomic clock. As we discussed above, if a measurement leaves you in a more informed place than no measurement then you are moving forward.

Measurement instruments can be imprecise

You can determine how precise your measurement instrument is by taking multiple measurements in a row and observing how much the results vary. If they vary a lot you probably will want to take at least 2 or 3 measurements every time you use it and record the average score. An example of this could be scales. I have seen my digital scale vary up to 500 grams just by stepping down and back up onto the scale.

The variable you are measuring can fluctuate for reasons outside of performance changes

The physical world is messy. Even if you had the perfect measurement tool the fact that your weight is 72kg today and tomorrow 71kg doesn’t necessarily mean that your new diet is working. You may have lost that kilo because you went to the bathroom, you ate less or god knows what. A way of blinding yourself against spurious changes that only reflect random fluctuations is to take measurements across multiple days. Once you have your baseline you can start your new exercise or diet and get a more precise idea of whether it’s helping you improve or not.

Favor less precise and simpler over more precise but more complex

You are going to be measuring a lot. The less time you spend writing down numbers the more time you have to actually improve. Simpler tools or measurement procedures are less likely to fool you into thinking they are precise and will make you more likely to use them. For example, if you’re trying to get stronger arms you can think of two measurement methods:

- Measuring the size of your biceps in multiple places.

- Measuring the maximum weight you can lift with your arms.

If we ignore for a moment the fact that the second method is more correlated with strength than the first, with the first approach you may fool yourself into thinking that you have a more precise idea of how much you’re improving because you are recording more data but, as we have seen, every variable that we measure is going to fluctuate and the more variables you track the more spurious fluctuations you will observe.

Don’t reinvent the wheel

Look for existing measurement tools. They may not be exactly what you are looking for but, if they are close enough, using them saves you a lot of time and it removes a whole family of errors compared to doing it yourself. For example, Anki, a flash card program that helps you memorize anything, collects performance statistics about how well your memory is doing without you having to do anything.

If you run, bike or swim you should consider investing in any watch or device that allow you to export the data they collect to your computer to later graph it and do whatever you want with it.

For any time-based exercise a sports stopwatch works great.

Make sure that the variables you measure are correlated with your goal

For example, if you are trying to get ripped don’t measure the amount of weight you lift or even your absolute weight. A variable more correlated with being ripped is the body fat percentage. You could be increasing the amount of weight you lift by adding muscle mass and fat and get away from your goal of getting ripped. In every case try to think of variables that necessarily must change when you improve.

Track as few variables as possible

The Pareto Principle applies in deliberate practice and performance improvement, generally a few variables will tell you whether you are improving or not. Trying to add more variables is generally a sign that your exercises aren’t working and you are trying to “shoot the messenger”, your variable, by adding more that hopefully will tell you a nicer story.

When you reach a certain level the speed at which you improve decreases without you actually reaching a plateau. Given the norma fluctuation in variables that we have seen it may be useful in those cases to temporarily come up with secondary variables to more accurately see if a new exercise is working or if it’s not giving you anything anymore. For example, if you are trying to improve your reading speed you could measure number of pages read per 10min and complexity of the text as the primary variables. Once you read fast enough you may start or continue doing exercises like increasing the number of simultaneous lines read or eye fixations you could measure number of lines and number of surrounding words.

Monitor trends, not randomness

You measure in order to make decisions, to see progress and to spot plateaus. Collecting numbers and letting them rust has little value besides, possibly, motivating you to practice hard to make your numbers look good.

As we discussed above there is a lot of fluctuations in many of the variables that you will measure. For the same reason good investors don’t look at stock prices on a daily basis you don’t want to look at your measurements on a daily basis because there is too much noise and little signal. You should look at the trend over time.

Be systematic

Always measure in the same conditions to reduce variability and measure only changes in your skill or target goal. For example if you are measuring your weight always go to the scale at the same time of the day, preferably in the morning after going to the toilet. If you are trying to improve your arithmetic skills don’t measure the time it takes you to do one different types of exercises.

Takeaways

- If something matters then it can be measured.

- Any measurement that reduces your uncertainty is useful.

- Focus on the few key variables that account for growth.

- Test both variables and measurement instruments to know their precision.

More info

The book How to Measure Anything treats some of these and other ideas in more detail.

If you are curious to see what variables people are taking into account you may want to look at the Quantified self movement.

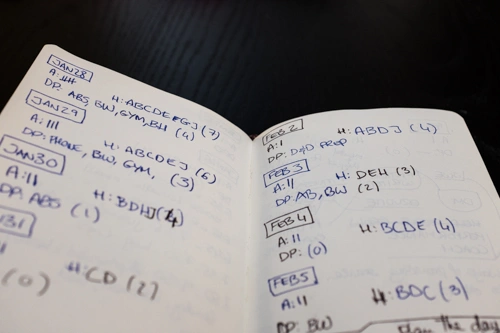

If you want to plot your data you can go as low tech or as high tech as you want. I personally combine both approaches: I always carry a Moleskine notebook with me where I jot down measurements of various things during the day. At the end of the week I enter those values into various CSV files and plot them with a statistical program called R but something simpler like a Google Docs or Office spreadsheet would also get the job done.